What is package lock json and how a lockfile works for yarn and npm packages?

14. März 2019

0 Min. LesezeitWhat is package-lock.json?

In this article, we will discuss both npm's package lock file `package-lock.json` as well as Yarn's `_yarn.lock`. Package lock files serve as a rich manifest of dependencies for projects that specify the exact version of dependencies to be installed, as well as the dependencies of those dependencies, and so on — to encompass the full dependency tree.

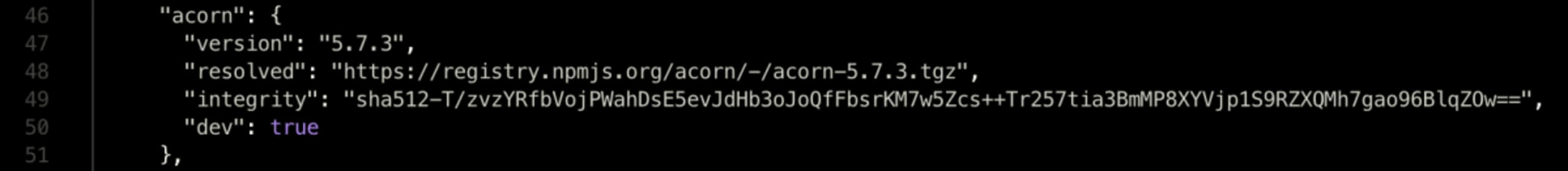

A package lock file is first introduced into a project when a fresh dependencies install is performed in that project. At the time of the installation, the entire dependency tree is calculated and saved to the lock file, along with metadata about each dependency such as:

The version of the package that should be installed

An integrity hash used to provide assurance that the package hasn’t been tampered with

The resolved registry location indicating from where this package was retrieved and from where it should be retrieved for future installs

Why do we need lock files?

Lock files are intended to pin down, or lock, all versions for the entire dependency tree at the time that the lock file is created. Why is it important to use a package lock file and lock package versions?

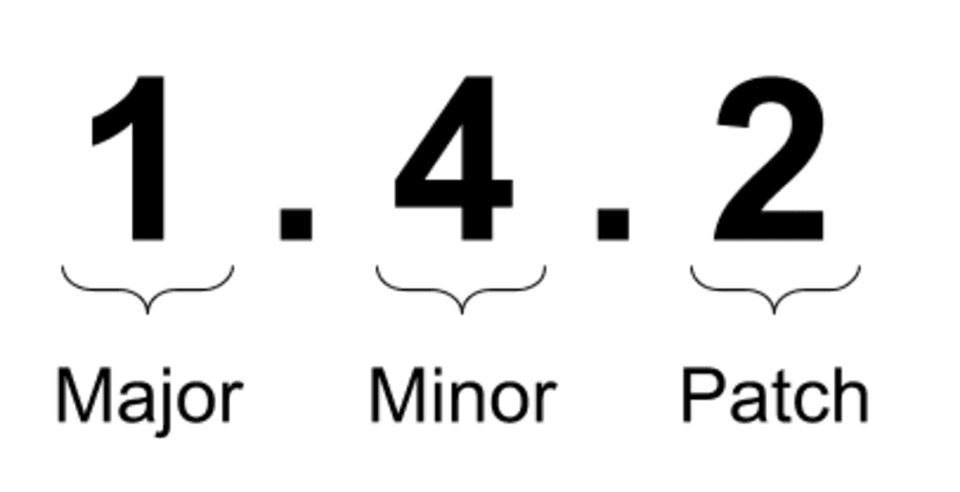

Without a package lock file, a package manager such as Yarn or npm will resolve the the most current version of a package in real-time during the dependencies install of a package, rather than the version that was originally intended for the specific package.

For example, if a project depends on package dummy-pkg: ^1.0.0 then two separate installs executed at different times could retrieve different versions of dummy-pkg. This can happen if a user installs `dummy-pkg`, which retrieved version 1.0.0 and then that package releases a new version 1.0.1 several minutes later. Thereafter, a second user running an install in the project would end up retrieving `dummy-pkg` version 1.0.1 instead of version 1.0.0.

Using lock files ensures that installations remain identical and reproducible throughout their entire dependency tree, across users, such as team members working together, and across systems, such as when running a CI build.

How do lock files work?

There are two package lock files that can be identified for the majority of the npm ecosystem:

Yarn’s yarn.lock

npm’s package-lock.json

There’s nothing like a good flow chart to explain how these two are used:

This illustration makes use of npm’s package-lock.json, but that can be substituted with yarn.lock everywhere. The only exception is that the npm client publishing process does not automatically ignore a yarn.lock file so it will be included in the packaged tarball unless explicitly ignored in the .npmignore file. However, as we see on the left side of the illustration, even if that package lock file exists as part of the package, it is not used for the end user consuming the library.

Both yarn and npm will never take into account lock files for transient dependencies; these are completely ignored by package managers. Only the top-level project, where an install action is performed, is looked up for its entire dependency tree through a lock file to which the package manager refers as the dependencies manifest.

Shrinkwrap lock files

Never say never. There is one case in which a special lock file exists that is taken into account even for transient dependencies. The npm-shrinkwrap.json file pins down the dependency tree like the other lock files do, but an npm publish process will also commit this file to the registry. More importantly, when end users consume the library in a typical application and run an npm install — the library’s shrinkwrap file will decide on which versions to pull instead of the semver resolution, which happens during installation.

It is important to note that yarn and npm differ in how they work with packages that have an npm-shrinkwrap.json, as follows:

npm will always place the dependencies specified in the

npm-shrinkwrap.jsoninto the package’s own level ofnode_modules/folder and will not try to flatten it up the tree.yarn will never take

npm-shrinkwrap.jsoninto account and completely ignores it.

What is a shrinkwrap file good for? Well, it allows library maintainers to pin down and curate their own library dependencies in order to ship known versions. It does, however, require careful maintenance for the entire dependency tree. Also, if a shrinkwrap file is used, there is no need for any other lock file to exist in the source control. A good example of a library that takes this approach is the well-known hapijs project.

Drifting lock files

Lock files are introduced when developers interact with a project, such as adding a dependency or installing dependencies for a pristine project clone. It is common practice for developers to add or remove dependencies from a project during the development cycle, but what happens if they make a change in package.json and forget to commit the relevant lock file?

When a project’s package.json is not in-sync with its lock file, package managers like npm and yarn will try to reconcile the difference and generate a new manifest. While this sounds like a good thing, it is actually a recipe for issues if it happens during CI.

If the build step doesn’t fail on a lock file drift from the declared dependencies in the package.json, it means that the artifacts being built or tested against will potentially use whichever version available at the time of the build, thereby contradicting all the benefits of a lock file.

It is thus recommended to advise package managers to use the lock file when installing dependencies, such as:

1$ yarn install --frozen-lock file

2$ npm ciLockfiles for applications and libraries

Opinions vary on how one should make use of lock files, depending on whether the project is the main application, or the project is actually a library that is meant to be consumed by an application or another library.

There is consensus on application projects using a lock file. Libraries as projects—not so much. Why is that?

The main argument against having lock files in libraries is that it will cause disparity in the dependencies that consumers actually pull with the library. Due to this disparity, package maintainers will not catch breaking builds.

However, by not using a lock file the dependencies will resolve only during installation time and will probably be different for maintainers and consumers anyway.

Personally, I see library projects as no different and should include a lock file for the sake of team member collaboration and reproducible builds.

Let me suggest an enhancement though—if you are truly worried about your library’s dependencies being broken for your users you can establish two different CI builds to flush these issues:

One to use the project’s lock file like any normal build configuration for a project.

The other—to ignore the project’s lock file and resolve dependencies according to their latest semver

This flow allows you to maintain reproducible builds and consistent dependencies for development workflow, and at the same time enables developers to catch any potentially breaking changes for your library consumers — and all of this, while also keeping all of the developers on your team happy.

Capture the Flag: Der Snyk Workshop

In unserem On-Demand Workshop erfahren Sie, wie Sie Capture the Flag Challenges erfolgreich abschließen.