Go security cheatsheet: 8 security best practices for Go developers

Gerred Dillon

9. Februar 2021

0 Min. LesezeitIn this installment of our cheatsheet series, we’re going to cover eight Go security best practices for Go developers. The Go language incorporates many built-in features that promote safer development practices — compared to older and lower-level languages like C — such as memory garbage collection and strongly-typed pointers.

These features help developers avoid bugs that can lead to exploits by removing the responsibility to self-manage memory. However, there are still security best practices that programmers should be aware of. This cheatsheet, authored by Eric Smalling, Gerred Dillon and with help from Dan Enman (Sr. Software Engineer at Snyk), addresses some of the more common topics.

Download the cheat sheet here!

Use Go Modules

Scan dependencies for CVEs

Use Go standard crypto packages

Use html/template to help avoid XSS attacks

Subshelling

Avoid unsafe and cgo

Use reflection sparingly

Minimizing container attack surface

1. Use Go Modules

The Go Modules system is the official dependency management system as of v1.11 with the older Vendor and Dep systems having been deprecated. Go Modules allow for dependency version pinning, including transitive modules, and also provides assurance against unexpected module mutation via the go.sum checksum database.

First, you should initialize your project by running go mod init [namespace/project-name] in the top-most level directory.

$ go mod init mycorp.com/myapp

This will create a file in the current directory named go.mod which contains your project name and the version of Go that you are currently using. Assuming your source code has package imports in them, simply running go build(or test, install, etc) will update the go.mod file with modules used including their versions. You can also use go get to update your dependencies, which allows for updating dependencies to specific versions, and this will also update go.mod.

Example go.mod file:

module mycorp.com/myapp

go 1.15

require (

github.com/containerd/console v1.0.1

rsc.io/quote/v3 v3.1.0

)

Notice that a file named go.sum was created as well. This file contains a list of hashes for each module used which is leveraged by Go to validate that the same binaries are used for every build. Both the go.mod and go.sum files should be checked into source control with your application code.

The tutorial Using Go Modules, found on the the official Go Blog, is an excellent resource for learning more about Go Modules including how to pin transitive dependency versions, clean up unused dependencies, and more.

2. Scan dependencies for CVEs

As with most projects, the amount of code in the modules that your application depends on often outweighs that of your application itself, and these external dependencies are a common vector for security vulnerabilities to be introduced. Tools like Snyk—powered by our extensive Vulnerability Database—can be used to test these graphs of dependencies for known vulnerabilities, suggest upgrades to fix issues found, and even continuously monitor your projects for any new vulnerabilities that are discovered in the future.

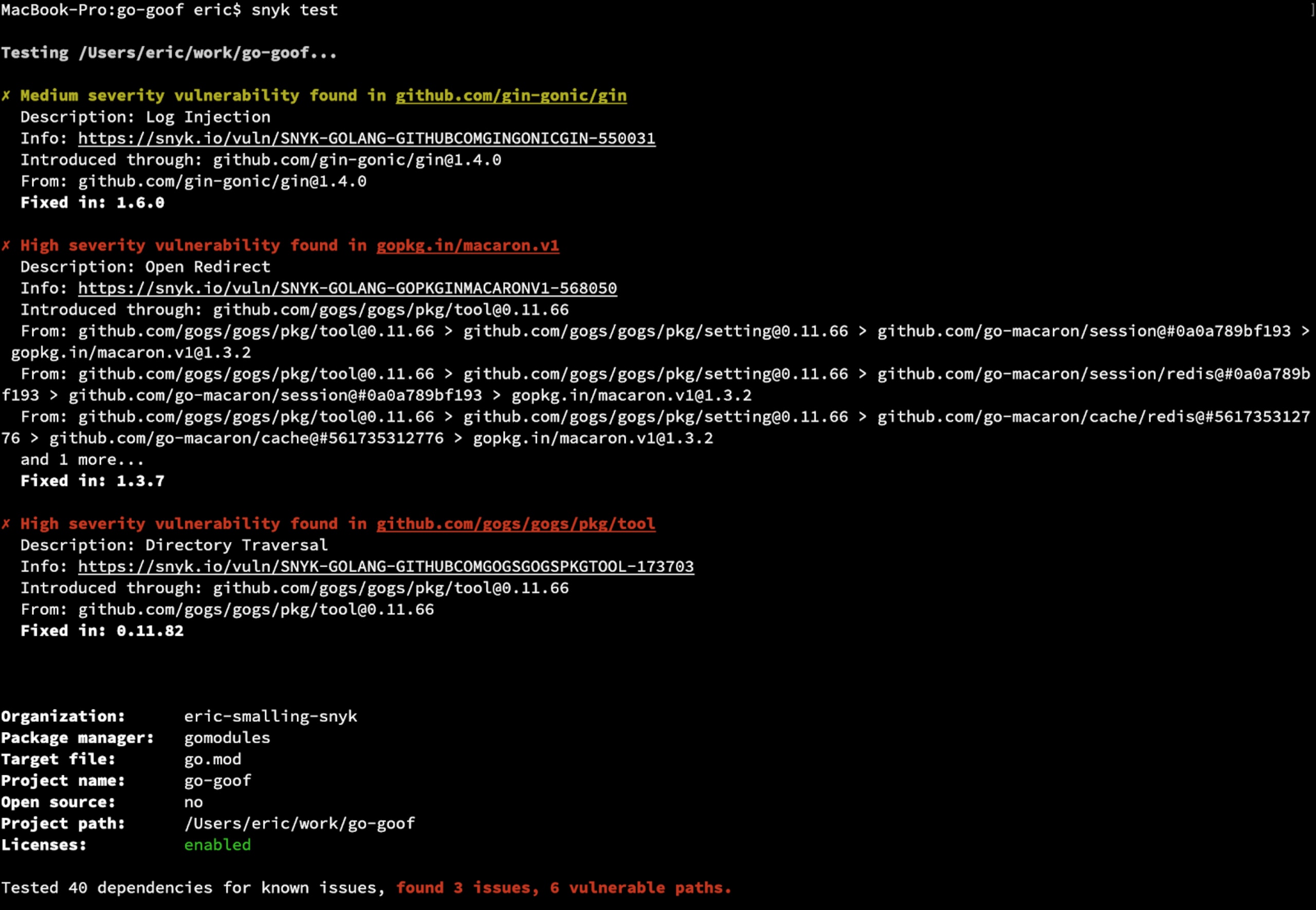

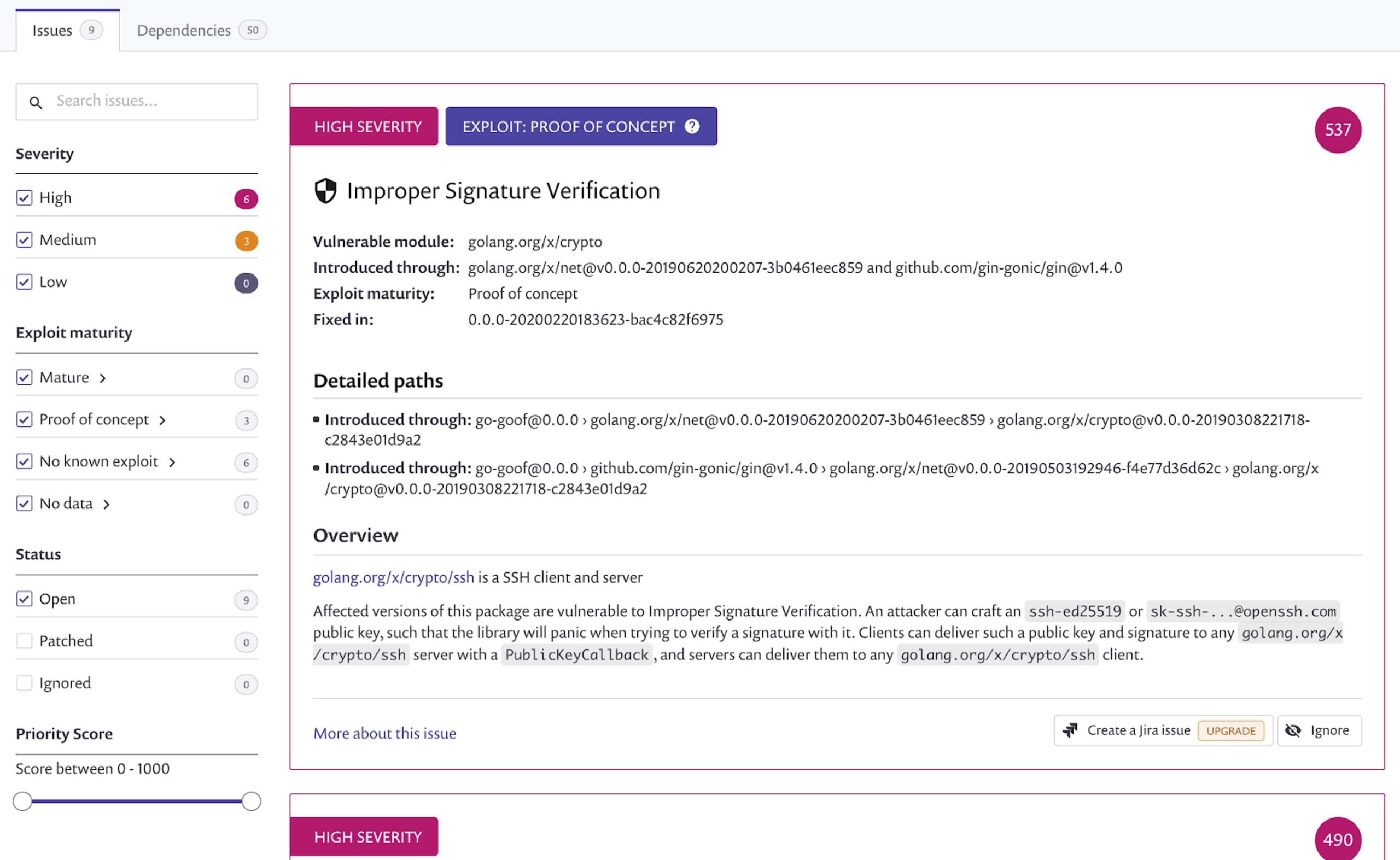

For example, simply running snyk test on a Go application will parse your modules and report back any known CVEs, as well as info about any fixed versions of them that you can upgrade to. Additionally, the Snyk web-based tools can monitor your GitHub repositories directly and continually, alerting you to vulnerabilities that are found in the future even if you haven’t changed your code or run a CI build on it.

3. Use Go standard crypto packages as opposed to third-party

The Go standard library crypto packages are well audited by security researchers but, because they aren't all-inclusive, you may be tempted to use third-party ones.

Much like not rolling your own cryptographic algorithms, you should be very wary of third-party cryptographic libraries as they may or may not be audited with the same level of scrutiny. Know your source.

4. Use html/template to help avoid XSS attacks

Unfiltered strings passed back to a web client using either io.WriteString() or the text/template package can expose your users to cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks. This is because any HTML tags in the strings returned will be rendered to the output stream without encoding and may also be sent with an incorrectly defined Content-Type: plain/text response header if it’s not explicitly set.

Using the html/template package is a simple way to automatically web encode content returned rather than trying to make sure you’ve manually done it in your application logic. The OWASP/GO-SCP documentation has an excellent chapter and example detailing this topic.

5. Subshelling

In Go, a subshell basically gives direct shell access to your system and its use is typically restricted to command-line tool type applications. Where possible, always prefer solutions implemented natively in Go code using appropriate modules.

If you do find yourself needing to use a subshell, take care to sanitize any external sourced data that might get passed into it, as well as the data returned, to ensure your application isn’t exposing unnecessary details about the underlying system. This care is similar to the attention you would give to attacks on rendered templates (see #4 above) or SQL command injections. Also consider that putting a call to run an external process as part of an application request thread could have other side effects that you cannot control from your Go code, such as changes to the file system, calls to external dependencies or changes to the security landscape that might block such calls—for example, limits imposed by running in a container or by tools like AppArmor, SELinux, etc

6. Use caution with unsafe and cgo

Much like the C language, Go supports the use of pointer type variables—however, it does so with strict type safety to protect developers from unintended or even malicious side-effects. In C you can always define the void* pointer which has no typing assigned; to do the same kind of thing in Go you use the aptly-named unsafe standard package to break type-safety restrictions. Using unsafe is generally discouraged in the Go documentation as it allows for direct memory access, which combined with user data can potentially enable attackers to break Go's memory safety.

Of similar concern is the use of cgo, a powerful command that allows you to integrate arbitrary C libraries into your Go application. Like any power tool, cgo must be used with extreme caution because you are trusting a completely external dependency written in an unsafe language to have done everything correctly; the Go memory safety net is not there to save you if there are bugs or malicious routines lurking in that external code. cgo can be disabled by simply setting CGO_ENABLED=0 in your build and this is usually a safe option to use if you don’t explicitly need it as most modern Go libraries are written in pure Go code.

7. Reflection

Go is a strongly-typed language, which means variable types are important. Sometimes you need type or value information about a variable reflected in your code at runtime. Go offers a `reflect` package that allows you to find and manipulate the typing and value of a variable of an arbitrary type, for example, to find out if a variable is of a certain type, or contains certain properties or funcs.

While reflection can be useful, it also increases the risk of runtime typing errors in your Go code. If you attempt to modify a reflected variable in a way that is not allowed (e.g. setting a value that isn’t settable on a struct) your code will panic. It can also be difficult to get a good grasp on the code flow, and the various type kinds and value kinds that are being reflected. Lastly, when working with reflected types or values, you may need to assert typings which can be confusing in code, and lead to runtime errors.

Reflection can be a powerful tool, but with Go’s typing and interface system, it should be rarely used as it can easily cause unexpected problems.

8. Minimizing container attack surface

Many Go applications have no external dependencies and are designed to run in containers, so we should strip down the filesystem available to them by using a couple of image building techniques. One of the easiest ways to do this is by using a multi-stage Dockerfile where we build the application in a build stage and then utilize a scratch base image for the deployment artifact image.

Take a look at the following Dockerfile example:

1| FROM golang:1.15 as build

2|

3| COPY . .

4|

5| ENV GOPATH=""

6| ENV CGO_ENABLED=0

7| ENV GOOS=linux

8| ENV GOARCH=amd64

9| RUN go build -trimpath -v -a -o myapp -ldflags="-w -s"

10| RUN chmod +x go-goof

11|

12| RUN useradd -u 12345 moby

13|

14| FROM scratch

15| COPY --from=build /go/myapp /myapp

16| COPY --from=build /etc/passwd /etc/passwd

17| USER moby

18|

19| ENTRYPOINT ["/myapp"]If you’re new to Dockerfiles, they are the step-by-step instructions that just about any OCI image build can use to build up the images; they are documented here. This example is a Multi-Stage Dockerfile, with two distinct stages: a build stage and the final, runtime image stage

Stage 1, lines 1–12: the build stage

Starting from the official golang:1.15 base image, in this stage we are setting some environment variables and building our Go application. When this stage completes a temporary image will be cached with a label of build that we can refer to later.

You are probably wondering what all of the environment vars and arguments we are passing into the build are:

GOPATH=””: Clearing out this var (which was set in the

golang:1.15base image) as it’s not needed when using Go Modules.CGO_ENABLED=0: Disablescgo(see section 6 above).GOOS=linux: Explicitly tells go to build for the linux operating system.GOARCH=amd66: Explicitly tells go to build foramd64(Intel) architecture.-trimpath: Remove filesystem path information from the binary.ldflag -s: Omit the symbol table and debug information.ldflag -w: Omit the DWARF symbol table.

This collection of settings will build, pretty much, the most minimal binary file possible but some of these may not be appropriate for your application, so choose as needed.

Stage 2, lines 13–10: the runtime image stage

In this stage, we simply copy the static binary and /etc/passwd files from the build stage into an empty, scratch filesystem, specify appropriate ownership and the command to run at container startup.

To build this image, we simply run the following from the same directory as the Dockerfile:

docker build -t [app image name]:[version tag] .

Note: the . at the end of that build line. It’s important, as it tells the build system where to find the Dockerfile and any other files it might reference.

The resulting image will have a filesystem containing exactly two files: our application and the passwd file that has our moby user (the name of the user is unimportant, we just don’t want to run anything as root in the container). There will be no sh, ps or any other files that an attacker can leverage. Of course, if you need other files for the operation of your application, you’ll want to include them or mount them at run time.

Download the Go security cheat sheet here!

Beginnen Sie mit Capture the Flag

Lernen Sie, wie Sie Capture the Flag-Herausforderungen lösen, indem Sie sich unseren virtuellen 101-Workshop auf Abruf ansehen.