How cloud transforms IT security into AppSec

March 12, 2020

0 mins readCloud computing is undoubtedly a seismic shift to the technology world, unlocking efficiencies and innovation like never before. However, it also drove another key change, which isn’t often discussed - cloud has made infrastructure a part of the application.

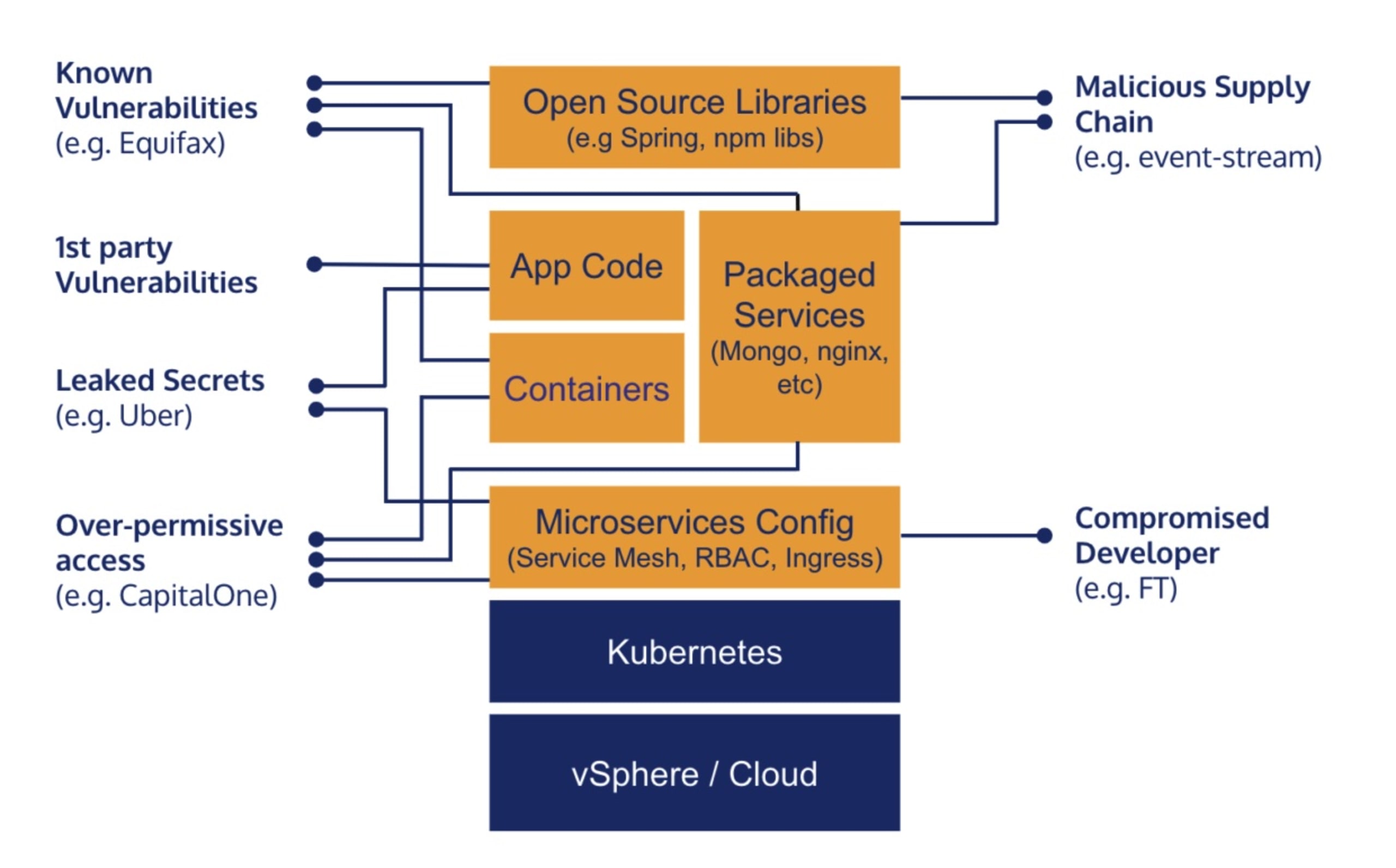

This shift carries significant ramifications for how we practice security. On the whole, security tools and practices today are designed for central IT and security teams, and are built to address those teams skills and environments. In cloud apps, decisions around network access, OS patching, access permissions, and more, are made by developers, not IT. They’re made individually for every application, not centrally. And they’re made constantly as part of the development process, not at specific review gates.

And yet, the security implications of these decisions remain the same. An open port can compromise a cloud VPC just as it could a data center network segment. An unpatched container can be hacked just like a bare-metal machine. The same risks apply, and are often magnified by the scope of the app.

For that reason, we need to rethink how to tackle these threats, but this time with an app context — different teams, different processes, different skills. In this post, I describe how the scope of the application grew to encompass infrastructure, and dig into the security ramifications. I believe this perspective is helpful when designing your security practices, picking your tools, and organizing your teams.

Style note: I’m using the word “Cloud” to represent not only cloud computing, but also containers, serverless, and many following technologies. I also talk about “before and after” cloud, while in practice few enterprises are on a journey in between. This simple view is intentional, to help paint the bigger picture — I’m well aware this is a complicated world!

Applications in the pre-cloud era

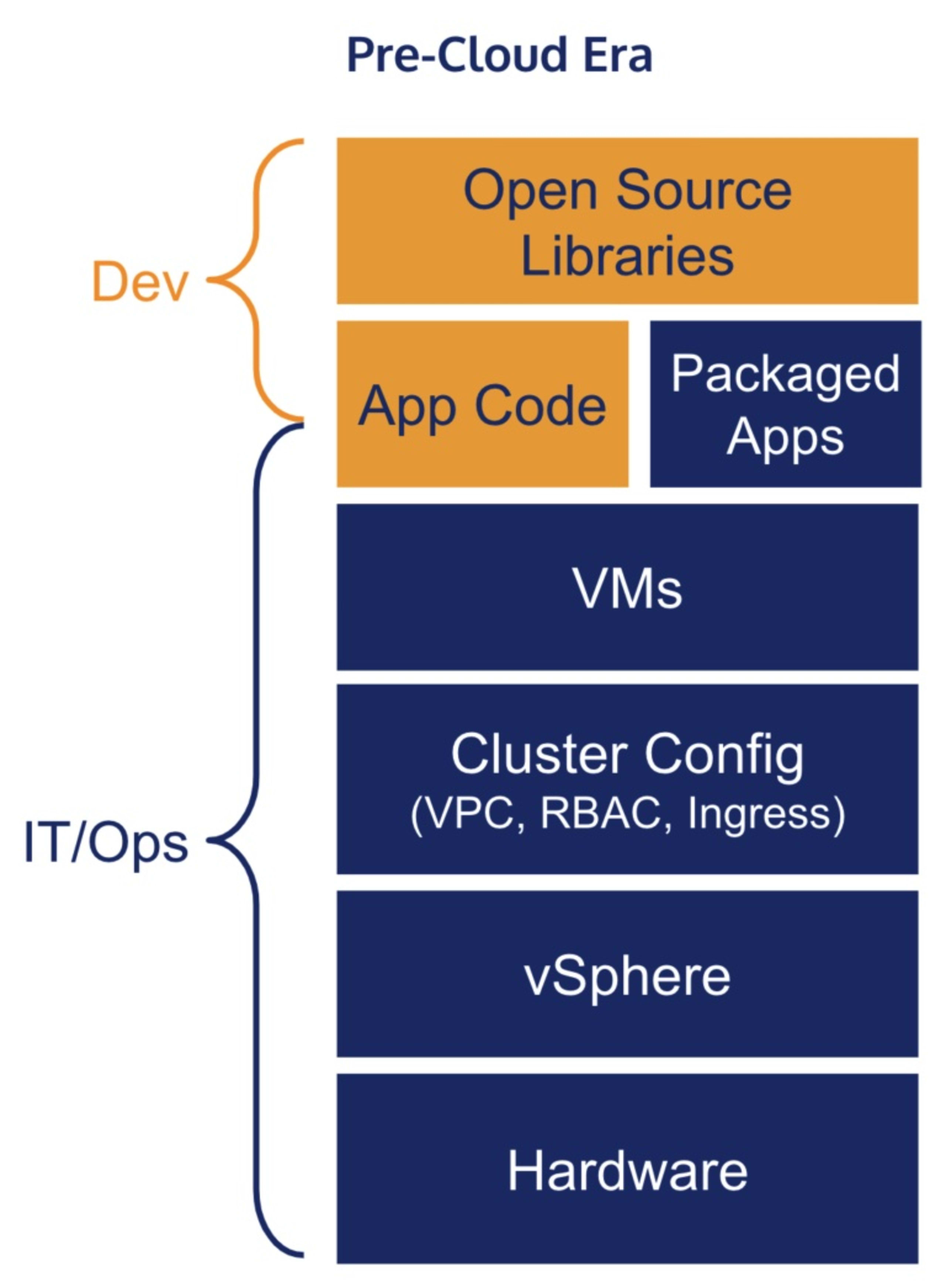

Before the cloud, applications were built on a hefty IT stack. I’ll refer to this period in past tense, though in practice most enterprises still operate primarily in this fashion.

You had a data center where central IT carefully managed capacity and allocated resources. Companies had to manage their amount of rack space, buy servers and bring them online, manage hardware failures and track which server is used by whom. If an application needed a server, it required paperwork and approval, as another server meant either spending more money or not giving a server to someone else.

When virtualization came along, another IT layer came in, typically vSphere, managing virtual machines on top of the physical ones. This increased efficiency, but didn’t change the core process — capacity was still limited and shared, so getting a server meant filing a ticket, and a central IT group had to manage both server capacity and the virtualization layer on top of it.

Beyond the servers, IT also managed networks. Those were configured using physical switches and routers, and focused less on capacity and more on access controls — which users can access the network, and which networks can interconnect. Networks are often complicated — so, again, central IT played a key role, managing complicated communication permissions across the data center, as well as allocating bandwidth.

Beyond hardware, IT also managed central resources. One such resource was golden images for virtual machines. These golden VMs held approved software, scrutinized for legal, security and overall quality purposes. Central IT also monitored these VMs, updating them for vulnerability fixes or corporate policy changes. Applications were installed over these VMs, often manually, and were restarted as necessary to accommodate such updates.

Managed services were another example of a central resource. For instance, it is possible IT managed a big central Oracle database, which the applications required to function. One or more DBAs (Database Administrators) would manage indexes and tables, working with different application teams as needed to tune them to their needs.

On top of all of those, sat the application itself. Applications were made up of code and libraries, and had to be deployed in very specific surroundings to work. Any change to their hardware, base VMs, DB usage, CDN or any other aspects required filing a ticket, and waiting.

Back then, that made sense, because the resources were limited and had to be shared. Adding physical capacity — whether its servers, network or storage — took substantial time and money. Implementing or extending a central application required significant effort from central IT, another shared resource where growing capacity is slow and expensive. And so, if one application got a bigger share, another app got less — a zero-sum game.

Applications in the post-cloud era

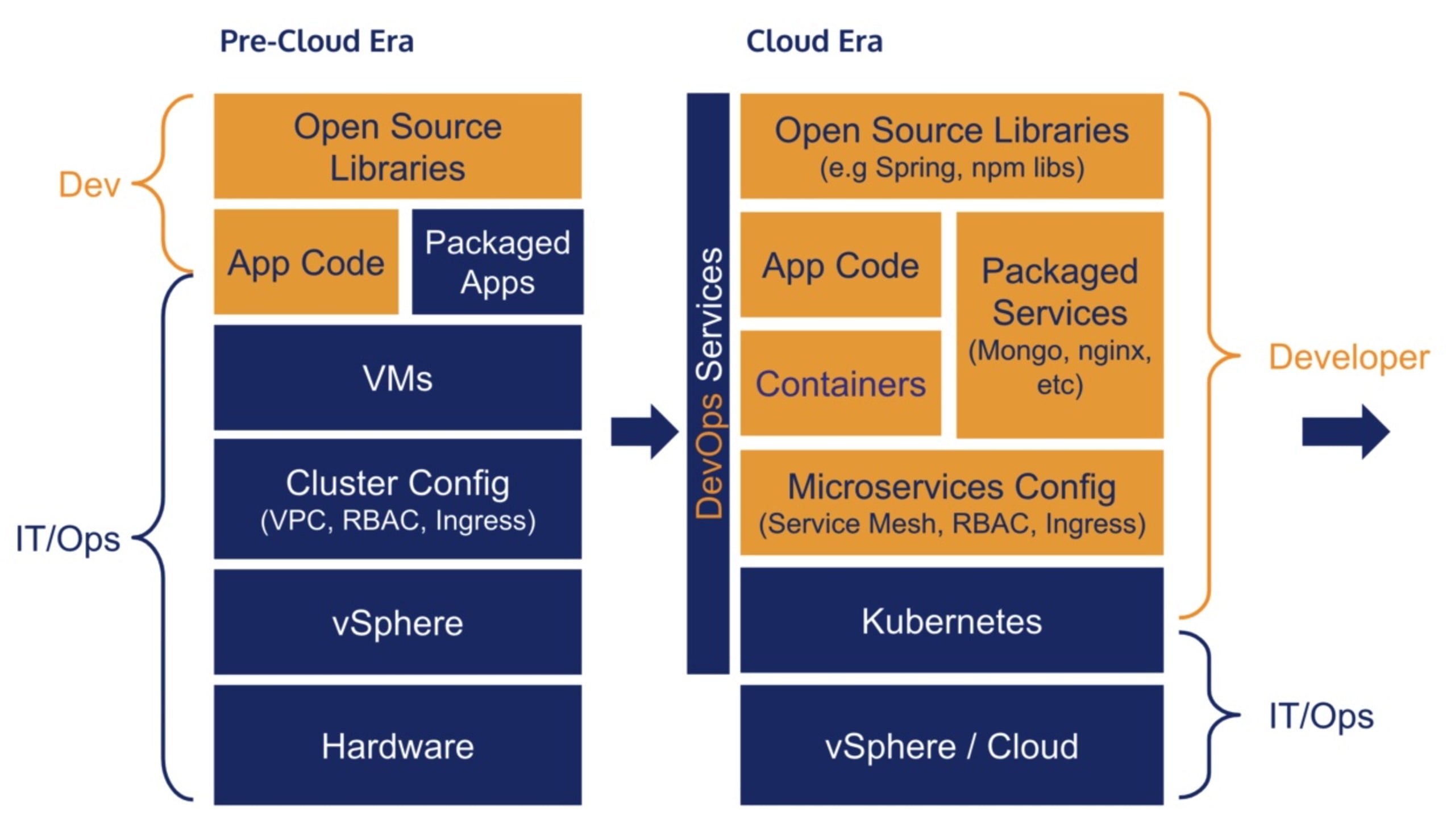

Then, the cloud arrived, and eliminated these constraints.

Hardware capacity became a non-issue. Developers only need access to a cloud account, and can then provision as many servers as their budget allows. These servers elastically grow and shrink using self-serve and software-driven controls, without any involvement from central IT.

Networks are no longer dependent. Application teams can create their own Virtual Private Cloud (VPC), which the cloud platform ensures is separated from the rest. Access to these networks is granularly set, based on the application’s needs, and configurable purely in software — self-serve.

While cloud VMs are less centrally-managed than their data center predecessors, containers truly severed this tie. Instructions for building containers are typically defined in a source code repo and built with the app, making it hard for central IT to get visibility into them and, practically, impossible for IT to patch them. Even centrally-managed “golden images” lose their appeal, as patches to those images don’t apply until an app is rebuilt, and developers increasingly rely on external base images.

Central applications were replaced by easy to use services built into the cloud platform, such as databases, authentication, messaging, and many more. Unlike most central apps, these services are API-driven and designed for self-serve provisioning and consumption by dev teams. Packaged containers replaced smaller applications, easily consumed out of Docker Hub to be just another microservice amidst the app’s topology. In both cases, the need to file a ticket and wait for limited IT resources to provision your app is nowhere to be seen.

Lastly, DevOps teams (sometimes named SRE or Platform) were created, replacing central IT with aligned ops teams. These teams don’t attempt to control the infrastructure that applications use, but rather provide tools and services, such as Kubernetes, that allow developers to independently operate these infra layers built into their apps.

Securing infrastructure as application

Over time, the cloud eliminates the need for most centrally managed infrastructure. Instead, that infrastructure becomes a part of the application itself. This trend is inevitable to continue, as we see CDNs, API gateways, middleware and more become a part of the application, improving the dev team’s independence and speed. This change started in public cloud, but in practice evolved into the private cloud too, as it mimics the same practices.

The security concerns, however, have not gone away.

An unpatched container can be hacked just as easily as a neglected VM or bare metal machine. A needlessly open port can give an attacker access to sensitive data regardless of where it’s hosted; and unencrypted data in the database can see it compromised very quickly, especially if stored on a shared service. The same attack vectors apply and we should keep an eye on those security concerns while taking measures to protect our applications.

What needs to change is how we defend against these infrastructure threats.Today’s solutions and practices are designed for central IT teams, not independent application teams. They are sometimes retrofitted into a shape that separate teams may use, but it’s quite rare that they truly fit that use-case.

We need to embrace a new perspective, built on this new reality of “infrastructure as application”. Such rethinking is a big task, and not one I can summarise in a few simple bullets, but here are some examples of changes to consider:

Reconsider your security org structure for securing cloud products. Security for IT stacks was designed to partner well with the IT org structure, but security for application stacks should be structured to work with the development organization. I have much more to say about this topic, but that will likely be a post on its own…

Understand the application developer's needs. Take the time to understand their reality, not just their technology, and aim to adapt your practices, tools and expectations to match theirs. The industry best practices are often based on the needs of IT, not dev, so don’t rely on them.

Don’t assume your existing pre-cloud solutions are the right ones for cloud apps. While keeping the same tools across your old and new stacks is convenient, it’s unlikely they will serve both realities well. Check what other tools your vendor has to offer — or other vendors around — and choose the right tool for the cloud environment.

Invest in flexible, API-driven, self-serve security tools. IT teams are a central function, allowing you to invest more time in custom integration. Dev teams and stacks vary significantly more. Invest in tools that can adapt to different surroundings, while providing similar security controls and governance.

This transition won’t happen overnight. In a decade, pre-cloud apps will be deemed legacy, like mainframe surroundings today, with their legacy security controls. Now is the time to start building your new security generation.